Goodbye to Ne Win

Asiaweek, 5 August 1988.

To most Burmese, their undisputed leader of the last 26 years had seemed an immovable fixture. Commonly referred to as "No. 1," Gen. Ne Win, 77, ruled his socialist police state with a will as tough and unbending as Burmese teak. But as any good Burmese Buddhist knows, all thing are transient, even strongmen. At an emergency meeting of the country's only political party, the Burma Socialist Program Party (BSPP), Ne Win stunned the more than 1,000 delegates, and the nation, by announcing his resignation as chairman and his retirement from politics. In his wake, he left an economy in tatters and a restive and disaffected population; well over 100 people have already been killed in riots in this year. Most of all, Ne Win left a tangle of questions for his countrymen over what might happen next.

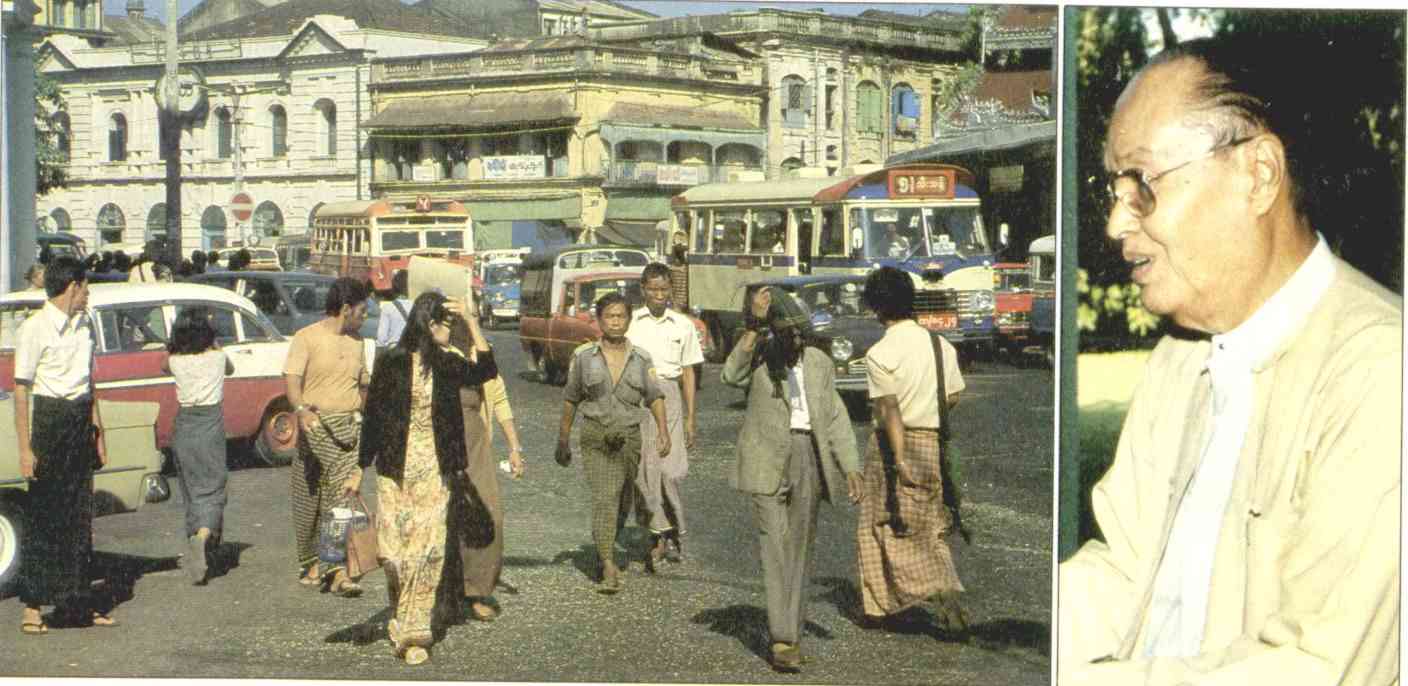

If, as some suspected, the wily ruler was angling for an outburst of popular clamor four him to stay in office, he may have miscalculated. Certainly, many speakers rose to prise him and insist that his continued rule was indispensable for the nation. IMPLORED TO RECONSIDER, ran the headline in one state-controlled newspaper. Sweeping economic reforms that his men unveiled were enthusiastically received. Two days after his speech, however, the congress accepted his resignation and that of party vice-chairman San Yu who had succeeded Ne Win in 1981 as president of Burma. The congress also took the virtually unprecedented step of rejecting a proposal of Ne win's: he had called for a referendum on setting up a multi-party system in place of the only game in town, the BSPP. On the streets, no masses poured out to plead that their ruler stay on. The capital, Rangoon, displayed only a tense and expectant quiet. to one Western diplomat, the acceptance of Ne Win's resignation coupled with the rejection of his referendum was "a slap in the face for him."

A day later, the BSPP's top body, the Central Executive Committee, selected a close ally of Ne Win's, Sein Lwin, 64, to replace him as chairman. That choice had immediate implications for the government's approach to any further disturbances. Considered among the hardest of the hardliners, Sein Lwin was in charge of the riot police that ruthlessly suppressed student-sparked protests in March and June. Sources say that in debates in the Central Executive Committee after widespread rioting June 21, Sein Lwin argued: "With the death of a few, everything is quiet. If we kill another 10,000 we will solve the problem for good." Sein Lwin also commanded an army company still remembered for killing 22 students during protests at Rangoon University shortly after Ne Win took power in his 1962 coup. Those who have met the new chairman say his manners are crude and unpredictable. Reportedly, he hs no formal education beyond the free elementary-level teaching offered by monks.

The sudden rise of Sein Lwin, No. 4 in the party hierarchy and No. 3 on the governing State Council, left open the question of how much influence Ne Win had on the choice. Although supposedly retiring from politics, the old warhorse gave strong indication in his speech July 23 that he did not want to leave the scene completely. In stern tones, Ne Win emphasised that only he could give the orders for the army to intervene to suppress disturbances. He did so, he said, in his home town of Prime in July and warned that he would not hesitate to call out the army again. Said he bluntly: "I am reigning from politics, but I will not allow chaos in the country. In this connection, I want all the people throught the country to know that in the future if there are any disturbances, as you know the army shoots straight. It does not fire into the air to scare."

Ne Win personally took some of the responsibility "even if indirectly" for what he termed the "sad events that took place in March and June." Curiously, however, this section of his speech, which also contained his resignation, was read not by Ne Win but by another, unidentified man to whom the chairman turned over the microphone for a short period. To some Burmese analysts, that indicated that Ne Win could choose to dissociate himself from the blame-taking sentiments.

Ne Win gave advancing age as his reason for retirement, pointing to party rules that allow members to resign only because of age or health. He is believed to have been in poor health for several years and to have made several trips to Europe and the U.S. for medical reasons. Still to emerge was whether he would retire to his lakeside villa in Rangoon or, as some speculated, move abroad. If he should choose exile, it would probably be in Switzerland, where he apparently keeps a house. He reportedly owns another home in the London suburb of Kingston, where Burmese dissidents have at times daubed protest slogans, although this house is also said to be an official residence.

The congress declined to accept resignations of four other senior party officials Ne Win named, including Sein Lwin, allowing only San Yu's to go through. Left in place was party general secretary Aye Ko, also vice-chairman of the State Council, who theoretically was next in succession before Sein Lwin. After the new party chairman was named, the Central Executive committee announced the Prime Minister Maung Maung Kha, 68, had been dismissed from the post he held for eleven years. State radio said he should take the blame for the March disturbances. Some analysts believed that he was Sein Lwin's main rival for the top party post.

A major nemesis at the congress was Brig.-Gen. Aung Gyi, who had recently issued a series of daringly critical open letters to Ne Win. The tone of attacks by Ne Win and many delegates, noted one analyst, was not just a scolding for an erring subordinates but a denunciation of a serious rival, even a traitor. A former Ne Win colleague, Aung Gyi resigned from the Revolutionary Council in 1963 when its policies veered off in a strongly socialist direction. But Ne Win told the congress that Aung Gyi resigned not because of policy differences but because "he gave the orders to blow up the student union." That was a reference to the destruction of the Rangoon University Students' Union in 1962 soon after the 22 students died. Other speakers claimed that his letters exaggerated the casualties from the recent riots in order to make trouble.

At his elevation, Sein Lwin wholeheartedly backed the economic reforms approved unanimously by the congress. Implementing them, however, will be at all order. They are nothing less than a total repudiation of Ne Win's isolationist "Burmese Road to Socialism". Nearly a year ago, after admitting mistakes, Ne Win began instituting some capitalist-style reforms, especially in the critical rice trade. But the latest measures would open virtually all areas of Burma's economic life to private enterprise, excluding only oil production, armaments, jade and gems.

Joint ventures between private and state-owned concerns and with foreign firms would be allowed. Steps would be take to restore confidence in the banking system. All curbs, checkpoints and other barriers that hinder movement of goods in the country would be abolished. Print media would be opened to the private sector. Farmers would be allowed to purchase farm machinery and engage in all kinds of agricultural trade. the timber industry would be opened to the private sector. All forms of inland transportation would be privatized. Laws encouraging foreign investment would be drafted.

Under the proposals, noted one diplomat, "the economic freedom, apart from the few remaining controls, is almost comparable to Thailand's." But onlookers remained sceptical about the follow-through. Laws implementing the new policies had yet to be promulgated by the People's Assembly, which was to get down to business July 27. Moreover, the country has no real leaders other than those who are steeped in the old ways or have a vested interest in the country's "shadow economy."

Still, Aye Ko spoke candidly about economic rot to the congress, which was called to bring in the reforms a year ahead of schedule. The country's major industries -- oil, farming, fishing, and mining -- were all languishing for lack of investment and foreign currency to buy needed materials, he said. The balance of payment deficit was now in excess of $300 million and being financed through increasing borrowing from abroad. The fall in oi8l production had severely affected the transport of goods, leading to shortages and exorbitant price rises.

The deteriorating economy has been blamed for a rise in tensions of all types. Despite the surface calm during the congress, the U.S. embassy in Bangkok warned American citizens intending to visit Burma then to "exercise extreme caution." It noted that Monday, July 25, was an important Muslin holiday -- the celebration of Haj to Mecca -- and that some of the previous disturbances, in Taunggyi and Prime, had racial and religious overtones. About 3.6% of Burma's 38 million people are Muslims of various races. For this year's festival, the government restricted the ritual slaughter of animals -- long a point of friction with Buddhists -- to home instead of mosque. Leaflets alternately inciting Buddhists or Muslims to rise up against the other also surfaced.

As the week progressed, Rangoon's streets were largely free of security forces. However, residents said police were no longer patrolling some neighbourhoods for fear of being hit in the back by a junglee -- akind of home-made spear using umbrella or bicycle spokes tipped with poisonous insecticides or excrement. There were no other signs of unrest; universities have been closed since June. But to many Burmese, the potential for further troubles in their gentle country seemed, if anything, to be greater.

ASIAWEEK, 5 AUGUST 1988.