Asiaweek, 7 October 1988

'Unity' on All Sides

After days of frenzied bloodletting, a deadly calm had settled over Rangoon. Stunned by the army's suppression of street protest with bullet and bayonet, most Burmese stayed at home last week, venturing out only to shop. Outside, military vehicles trundled down the deserted roads: armoured cars, jeeps mounted with recoiless rifles and trucks carrying heavily armed troops. The soldiers seemed fit and in high spirits as they removed remaining bamboo barricades setup by neighbourhood vigilante bands. Downtown, there were house-to-house searches. When weapons were found, household members were arrested. Amid the tramping army boots and glistening weaponry, a few children took advantage of the empty street to fly small, square-shaped kites.

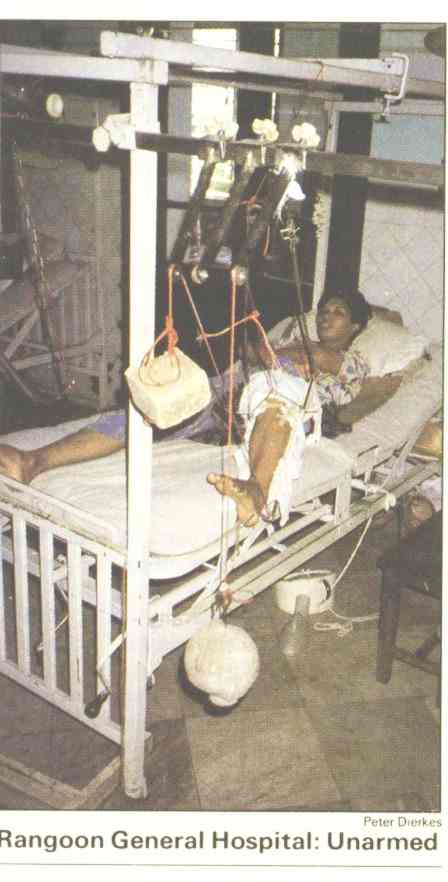

In the downtown district, the redbricked Rangoon General Hospital was eerily quiet. During the bloody mayhem following the Sept. 18 military coup by Gen. Saw Maung, the hospital had treated some 500 people, most of them for gunshot and bayonet wounds inflicted by soldiers. But a week after the clashes, the wards were virtually bare. A middle-aged nurse said patients checked out as soon as their injuries were treated, fearful that troops might roll up anytime to arrest or kill them. For the seriously wounded who remained, there were few facilities. Doctors were said to be buying antibiotics on the black market; minor operations were conducted without anaesthesia. A medical student in the hospital's intensive care unit bore five deep gashes on his body, including a severed artery in his right arm. He and 40 other protesters had been cut down by army gunfire near the Union Bank on Merchant Street. "We were completely unarmed and were demonstrating peacefully," he said bitterly.

The government gave the official toll for Sept. 18-26 as 342 dead and 219 wounded, with 1,107 arrested. But it said only three of the dead and seven of the wounded were female; an Asiaweek correspondent who visited hospitals and clinics in Rangoon last week saw many more women casualties. Diplomats believe the real figures are much higher.

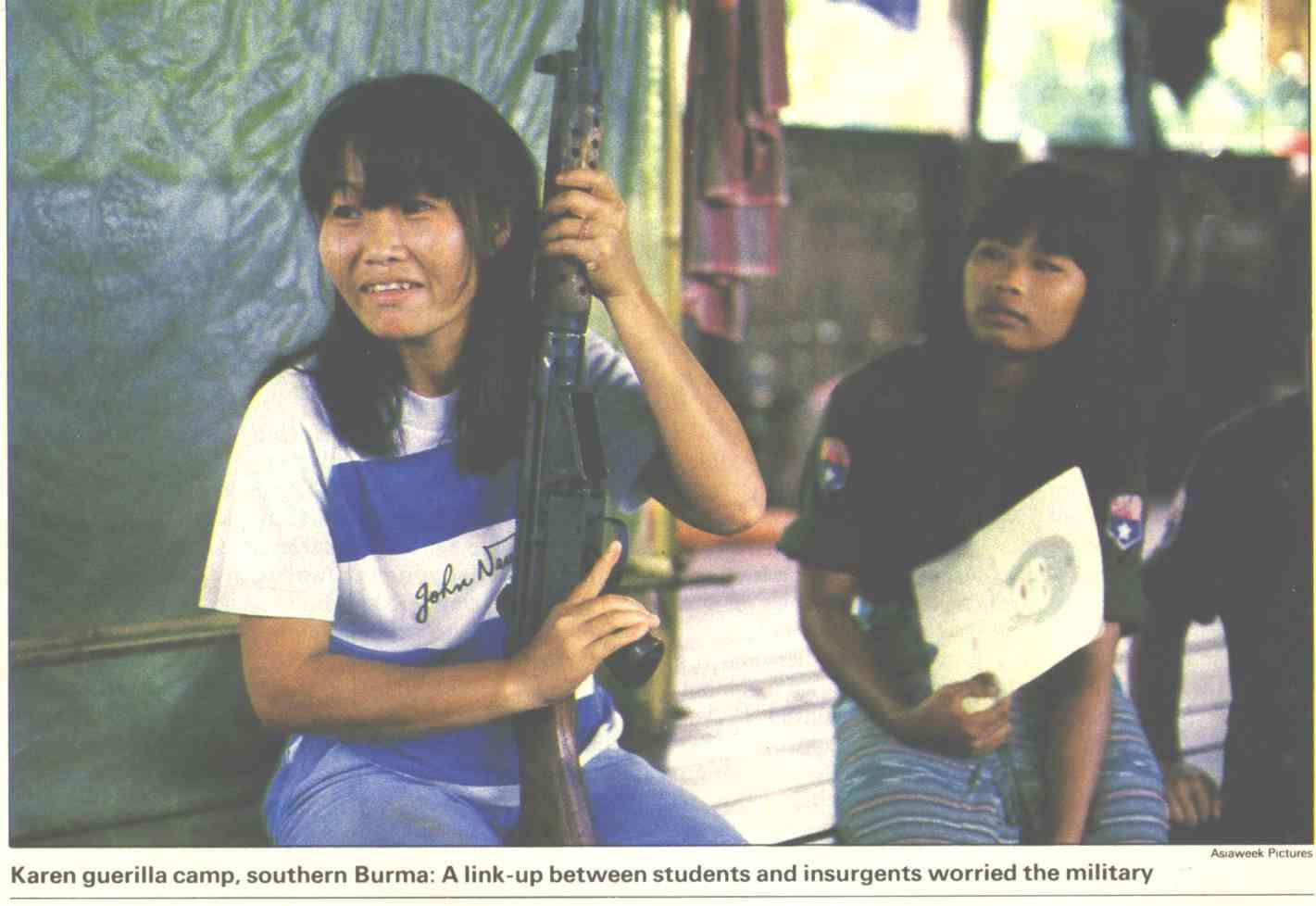

In the wake of the violence, more than 1,000 protesters, most of them students, were said to have fled to the jungles border areas controlled by various ethinc insurgent groups. Reports said about 700 demonstrators were staying with rebels of the Karen National Union (KNU) in various camp along the Thailand-Burma border; another 300 had made their way to the Mon National Liberation Army's headq2uarters at Three Pagodas Pass, about 300 km northwest of Bangkok. An Asiaweek source said 100 others had arrived at a Shan rebel camp near the Thai border town of Mae Hong Son. The anti-government protesters reportedly asked the insurgents for military assistance and training.

Those developments were a clear worry for the Saw Maung Government. Newspapers highlighted reports of students being nurdered while try to join the rebels. At the same time, the government said it was engaged in fierce fighting with about 1,500 Burmese Communist Party guerillas in northeastern Shan State, which borders china. Another insurgent attack by the KNU was reported at Maethawaw in the south. Sources in Rangoon said that with the border situation apparently worsening, troops had been moved from the now-subdued capital to the south. They said the junta had given priority to consolidating Rangoon, Mandalay, Moulmein and Meiktila against rebel activity, even at the cost of allowing the opposition to retain footholds in other cities. Clashes between people and soldiers were reported in the southern towns of Mergui and Tavoy.

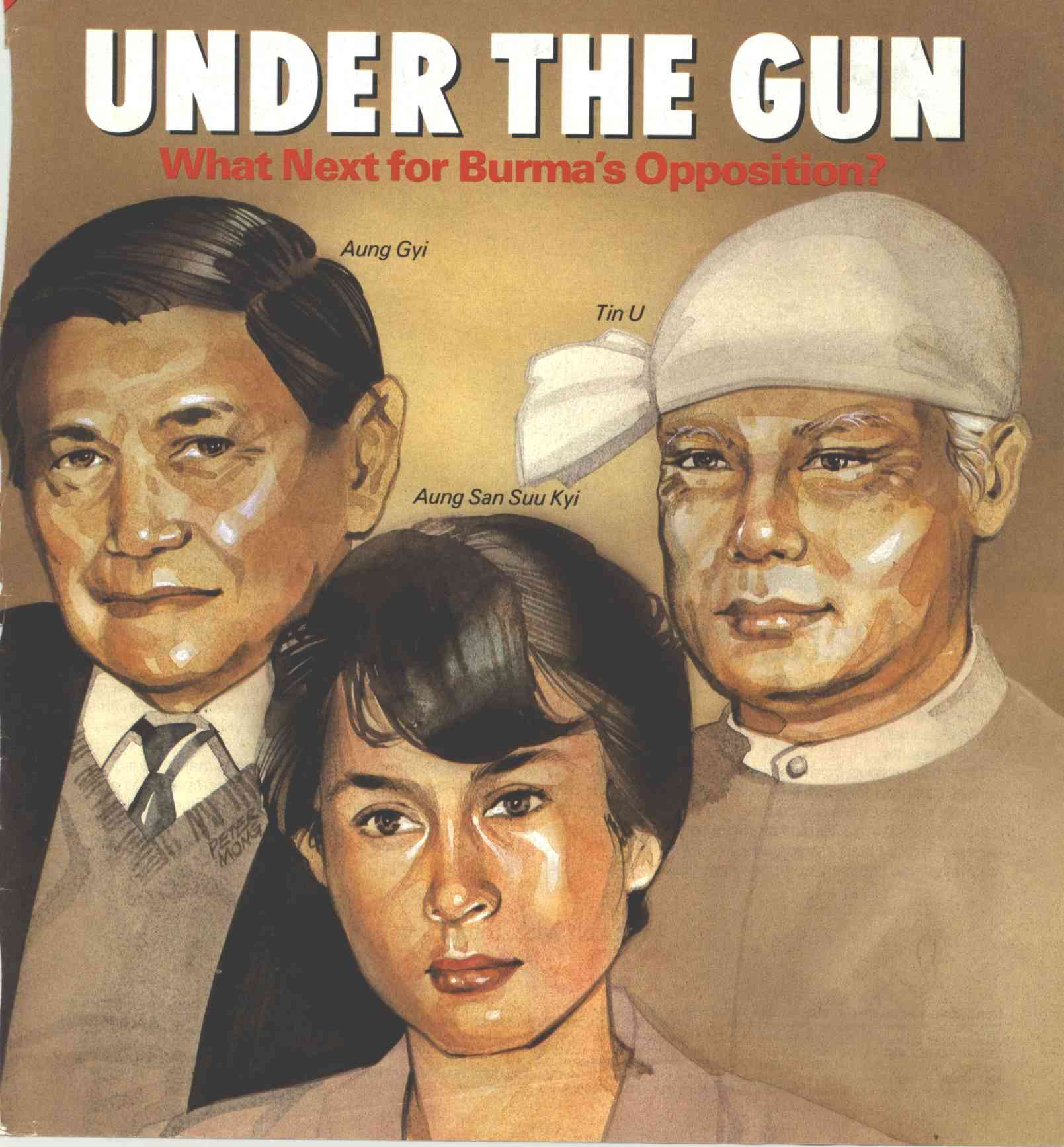

For Rangoon's nascent opposition leaders, the military's takeover from civilian president Maung Maung had been a jarring blow. It had come just as they were moving towards a coherent platform after a faltering start. Last week they regrouped. Top dissidents Aung San Suu Kyi, Tin U and Aung Gyi launched the League for Democracy(LD) to band together students, workers and monks fighting for democracy. Appointed general secretary was Aung San Suu Kyi (see interview), while Tin U and Aung Gyi were named chairman and vice-chairman respectively. Among other things, the League manifesto called for a continuation of the weeks-long general strike and the release of jailed demonstrators. But it did not demand a full accounting of the dead in the coup-inspired army killings -- an omission, some said, that suggested potential for an accommodation with the ruling group.

Indeed, the dissent trio seemed to be moving toward a reversal of their pledge to boycott promised multi-party polls. "The opposition is getting closer and closer to being able to take part in the elections," said a diplomatic source. He was confident that associates of ex-general Tin U had already made contact with the military regime on the issue. "If we do not acknowledge this government and their process, we will be automatically discounted," an LD aide was quoted as saying. "Our position is to beat them at their own game." Expremier U Nu, who had created a rift in the opposition by declaring an abortive provisional government in August, also seemed to be moving toward supporting the LD if it opted for participation. Sources said he had sent out feelers to the trio.

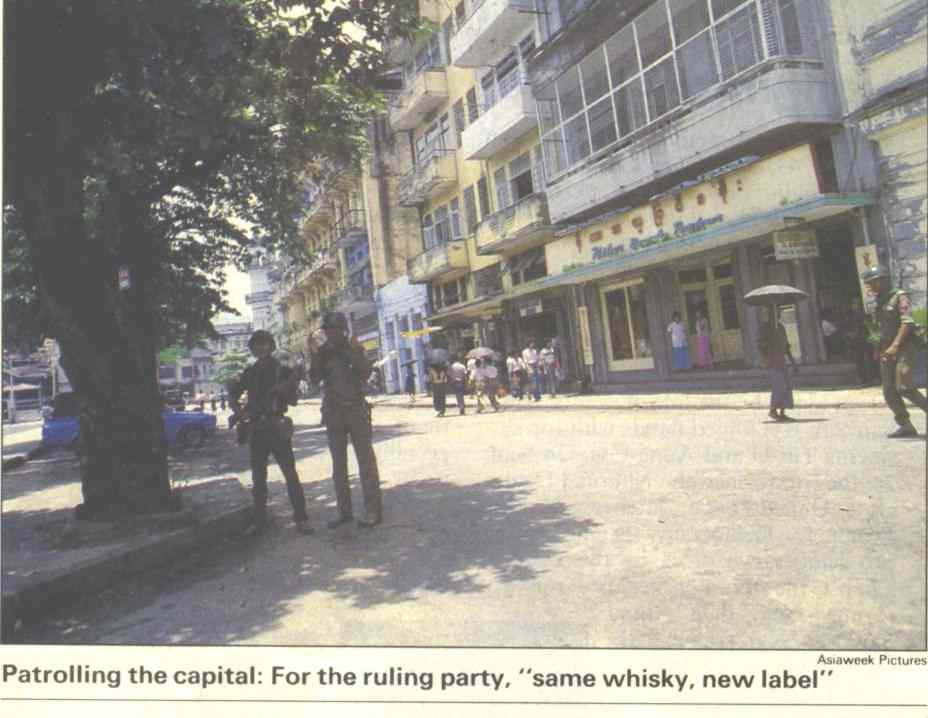

The League changed its name from the National United Front for Democracy when the old ruling party, the Burma Socialist Program Party, adopted a new, similar sounding title on Sept. 24. In an apparent effort to refurbish its image, the BSPP renamed itself the National Unity Party, dropping any mention of the socialism espoused by founder Ne Win, the longtime strongman believed still to be holding the reins of government. Few Burmese were impressed by the BSPP's new guise. "It's putting VAT 69 into a Johnny Walker bottle -- the same whisky, new label, " quipped a middle-aged worker in Rangoon.

Analysts reckoned the erstwhile BSPP, no longer the country's sold legal political grouping, wanted to reassert itself by winning the proposed elections. Ostensibly, the BSPP government was toppled on Sept. 18 by the men in olive. but diplomatic and other observers believed the putsch was staged on Ne Win's orders. The ruling military clique, the said, had simply stripped off its civilian facade. "The record shows that Ne Win has manipulated every election in Burma." asserted a Bangkok-based Burmese. "He will try to ram this election down the people's throats too."

An opposition decision to contest the polls may not go down well with the large segment of protesters who demanded that an interim government be formed first. That was a key opposition demand put forward first to Maung Maung and later to Saw Maung. Aung San Suu Kyi had herself earlier questioned the possibility of holding free and fair elections while the military was in control. She said last week that the time was not yet right for a decision on participation.

Many Burma-watchers wondered how dissidents could conduct an election campaign amid the ubiquitous military presence in Rangoon and other major cities. In the capital, troops were concentrated along the road to the airport and around Rangoon University, a hotbed of student dissent. The army had created safe enclaves in the city, some in suburban residences close to key buildings such as the Union Bank. Barracks near the Ministry of Defence were fortified by a new redbrick wall and main streets were crisscrossed with barbed wire. Armoured cars patrolled the streets and an 8 p.m. to 4 a.m. curfew was still in force. "It was like Beruit," said a recent arrival from Rangoon dramatically, if not quite fairly.

The next text was expected to come on Monday, Oct. 3, when the deadline was to expire for striking employees to return to work. The administration dangled a carrot by promising to pay September salaries to workers who attended office, and wielded a stick by threatening suspension if they didn't. "We think the people will go back to work long enough to collect their September salaries but then will probably go back home," said one Rangoon resident. A continuation of the general strike would be a crippling blow to the administration, already threatened with near-collapse of the economy. "The strike is very important," said Aung San Suu Kyi. No government can operate unless it can make the administrative machinery work. What we are doing is supporting the general strike."

But the immediate fate of Burma still seemed to hang on one individual. Said a Western diplomat in Bangkok: "The composition of the new government is not the issue with most people, who believe that no genuine change can occur unless Ne Win is removed." Numerous rumours in recent weeks that the 77-year old leader had sought political asylum have all turned out to be false. When asked why his country didn't take in Ne Win, a Soviet diplomat in Rangoon shot back: "Would you in my place?" To the president, the uprising was a personal affront, said one veteran observer. "Nobody has ever crossed Ne Win," he said, "and he is not about to let go of the power he has held for 26 years." But with the opposition slowly consolidating itself amid the country's continuing administrative and economic disarray, many Burmese believed a conclusion was in the offing. "I don't think the situation can continue indefinitely," said Aung San Suu Kyi. "Certainly with the next two or three weeks we should see something decisive.

REACTIONS

The World Slowly Awakes

The first bolldbath occurred on July 7, 1962, four months after Gen. Ne Win ousted Premier U Nu in a military coup. As thousands of protesting students gathered on the grounds of Rangoon University, Lt.-Lol. Sein Lwin gave the order to shoot. An estimated 148 students died in the massacre, earning Sein Lwin the nickname of "the Butcher". The killings set the pattern of ruthlessness for future crackdowns on opposition to Ne Win's iron rule. Students were slaughtered again during 1971 uprising at Moulmein, 170 km southeast of Rangoon; scores were gunned down by troops in the 1974 riots following the death of popular U.N. Secretary-General U Thant. Each time, the outside world watched in virtual silence.

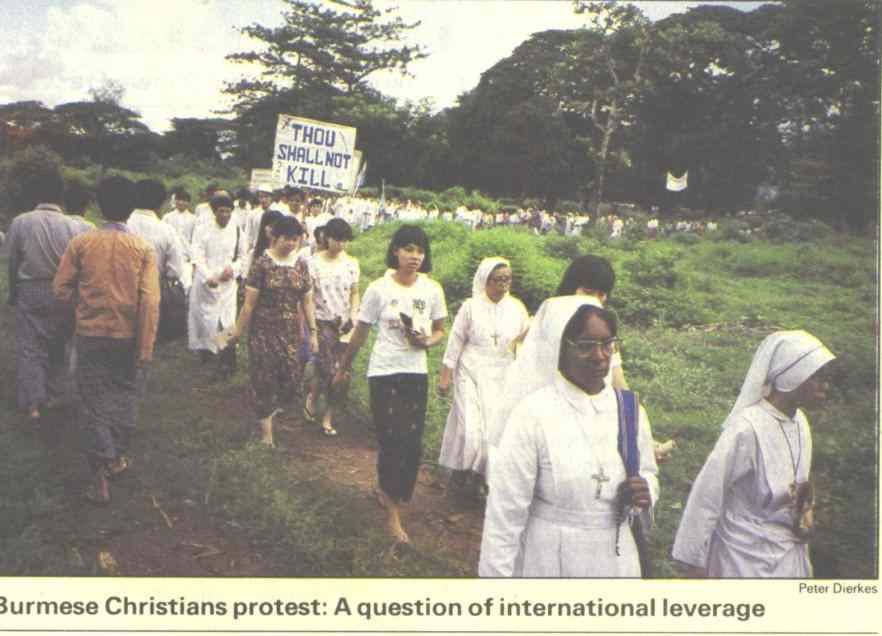

Burma's latest turmoil, too, initially evoked notably faint international reaction, even when up to 3,000 people died in the street mayhem of Aug. 8-12. "Perhaps it's because Burma has been out of the international picture for so long," observes an Asian diplomat in Bangkok. "Nations can afford to be quiet because Burma doesn't affect them so much." Only recently have foreign government begun voicing serious disapproval.

Among the first to speak out was West Germany. On Aug. 31, Bonn suspended all economic cooperation with Rangoon, terminating negotiations for new projects and for rescheduling the country's debt. Washington followed suit on Sept. 22 with a cut-off "for the time being" of all assistance, except for humanitarian purposes. The U.S. package of $14 million a year is minuscule, accounting for less than 1 % of Burma's foreign aid. But Washington provides valuable technological and agricultural expertise to the Burmese, as well as training for new recruits to the country's army.

The Americans' move may have been precipitated by an incident right on their doorstep Sept. 19, the day after Gen. Saw Maung's junta tookover from the civil administration of President Maung Maung. Antigovernment protesters swarmed through the streets of Rangoon, shouting defiance. Inside the U.S. Embassy, senior American diplomats, including Ambassador Burton Levin, watched in horror as troopers perched on rooftops across the road fired into a crowd outside. Unofficial estimates put the citywide death toll in two days at several hundred. Declared leading Burmese dissident Aung San Suu Kyi angrily: "I would like every country in the world to recognise the fact that the people of Burma are being shot down for no reason at all."

Finally, it seemed, the world had been shaken out of its apathy. In a statement issued in Athens, the European Community's twelve member-states expressed "deep concern" over the growing wave of violence in Burma. The EC called on political and social forces in Burma to "start without delay a substantial dialogue aimed at the restoration of democracy and the holding of free multi-party elections." Australia, India and Sweden also filed protest notes to the Burmese government. Even the friendly Soviet Union said it "regards the tragic developments in Burma with deep concern."

Two of Burma's neighbours, china and Thailand, have yet to issue formal statements. However, Peking's diplomats have expressed hopes that Rangoon would soon settle its "internal affairs." For their party, the Thais have built temporarily shelters in southern Ranong Province for more than 500 Burmese refugees; fourteen Thai MPs recently participated in a protest rally outside the Burmese embassy in Bangkok. But, officially, the Thai government has adopted a wait-and-see attitude. As one Thai foreign ministry official put it: "Burma is very close to our country so we have to be careful."

If any nation could pressure the regime in Rangoon, say analysts, it is japan, which contributes 80% of Burma's foreign aid. Not long after West Germany ended economic assistance, a leading Japanese financial journal quoted a high ranking Japanese Foreign Ministry official as saying that Tokyo would freeze a $248 million loan promised to Burma. No official announcement followed, however. "As to our relations with the new military government, we will be carefully watching developments," said Japanese Foreign Ministry spokesman Mstsuda Yoshifumi last week. "We do not have any concrete conclusions vis-a-vis the government of Burma." A senior European diplomat notes that Tokyo tends to favour the U.N. principle of non-intervention in internal affairs over that of upholding the universality of human rights. "Such a stand regarding Burma," he contends, "is absolutely horrifying."

But to what extent is Burma susceptible to leverage from outside? Many Burmese believe international pressure could force the military to accept opposition demands for democracy. Others, however, reckon such measures would be insufficient to dislodge a government controlled clandestinely by the still-powerful ex-president, Ne Win. Burma's political isolation over the past 26 years, they add, has sharply reduced the influence of major powers over the country's destiny. Indeed, Burma's opposition itself is wary of outside interference. "We want moral support," Aung San Suu Kyi told Asiaweek, "but we really don't want foreigners involved in this. This is a Burmese affair."

ASIAWEEK/ 7 OCTOBER 1988.